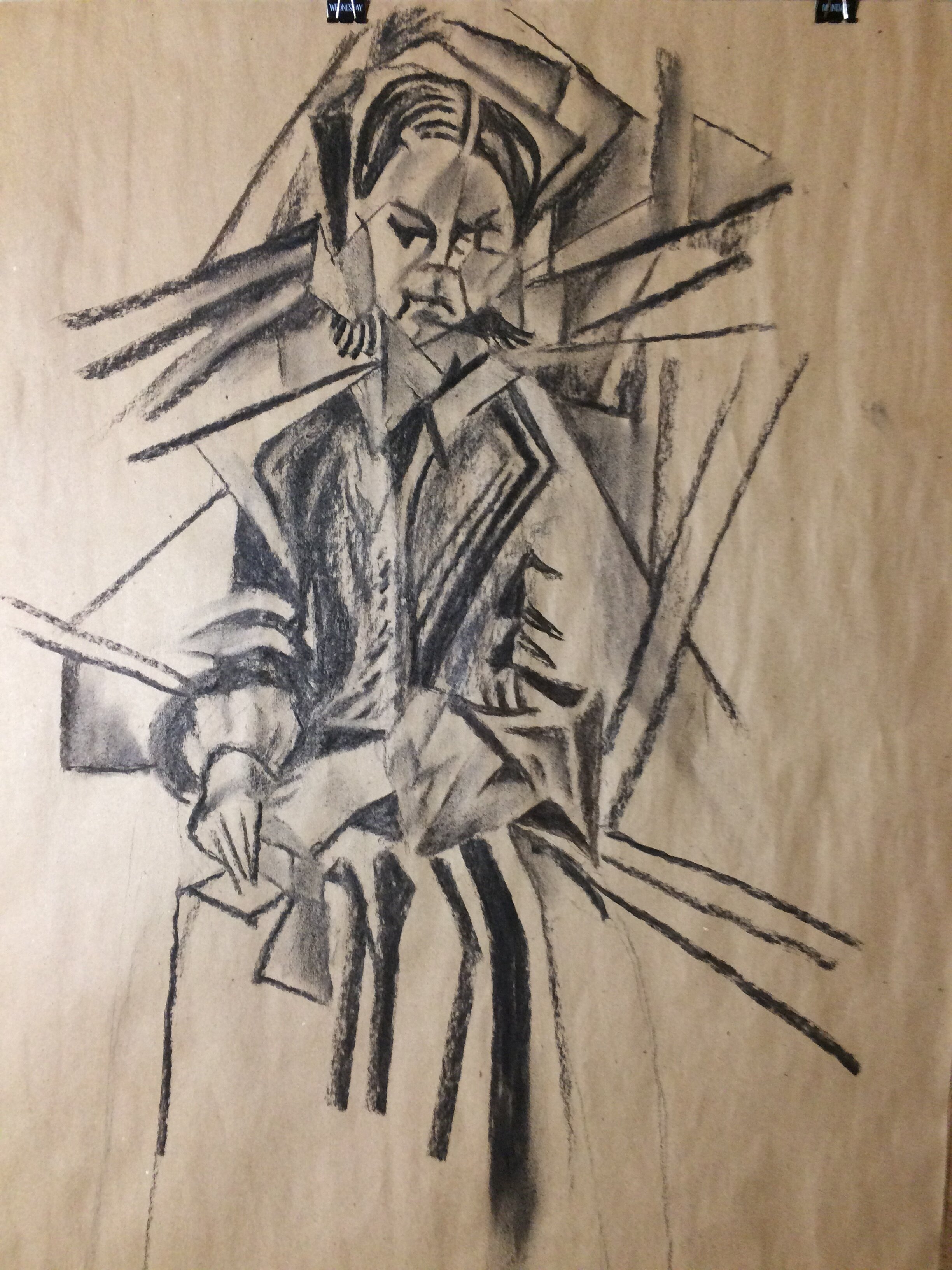

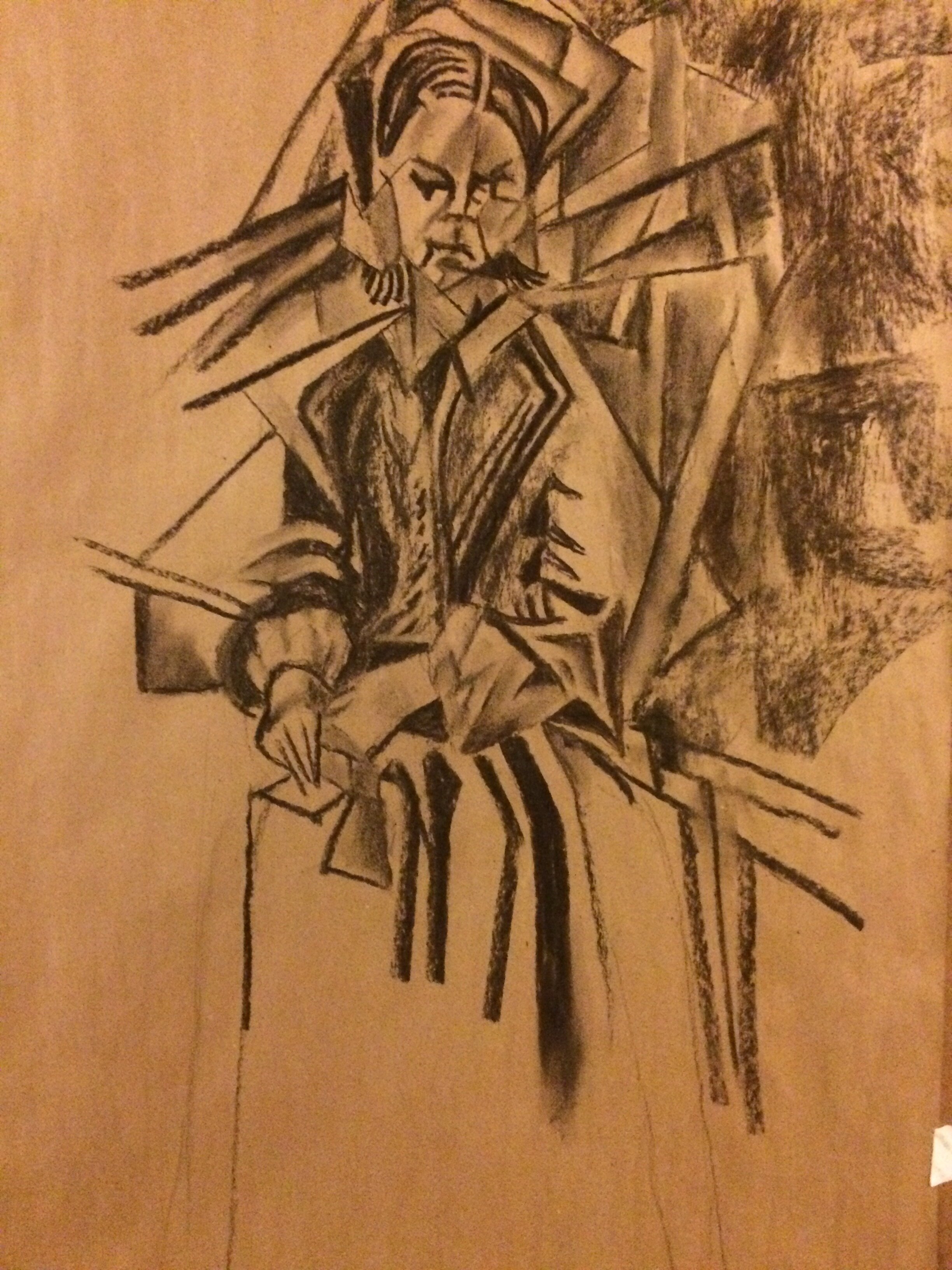

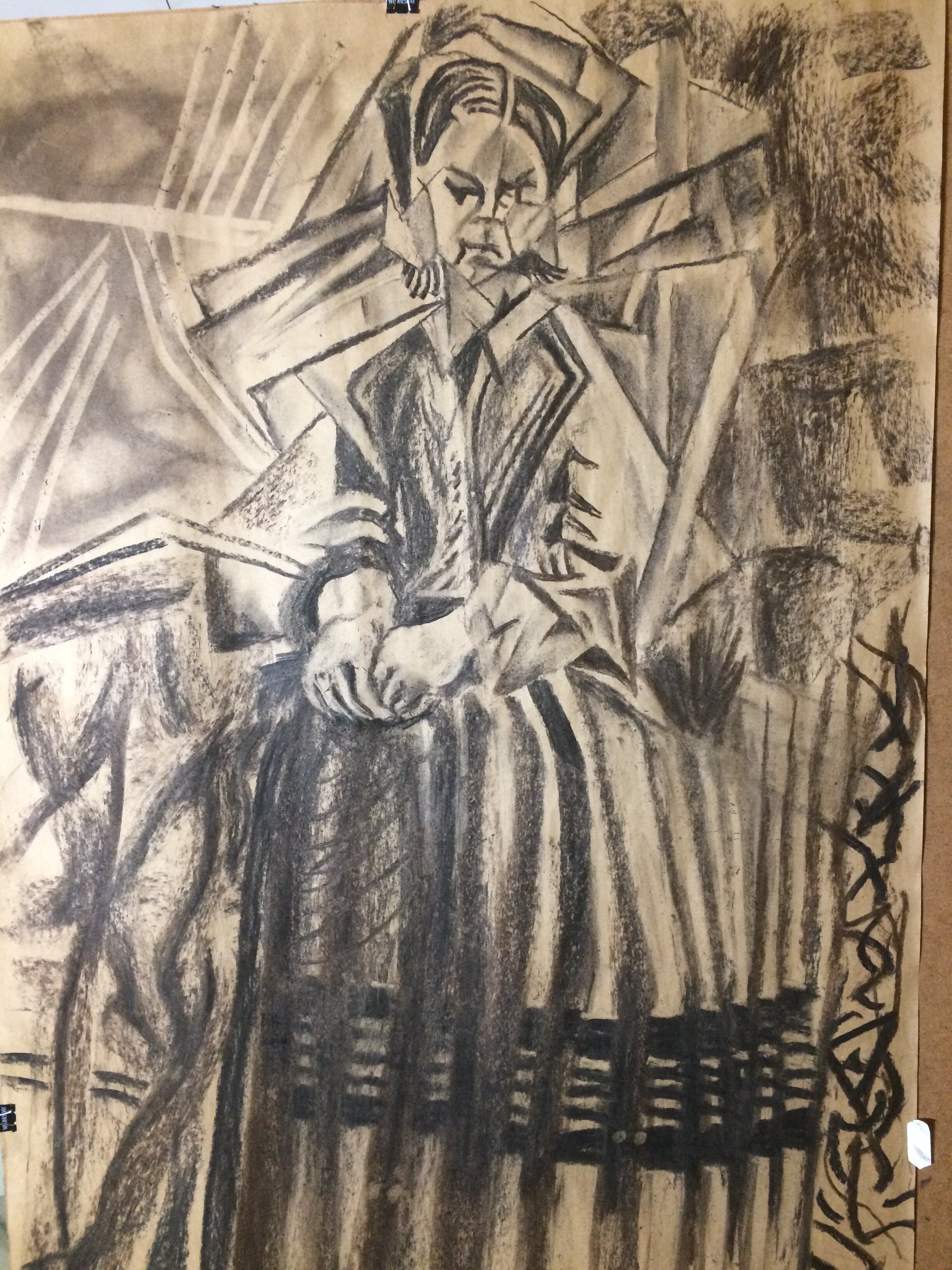

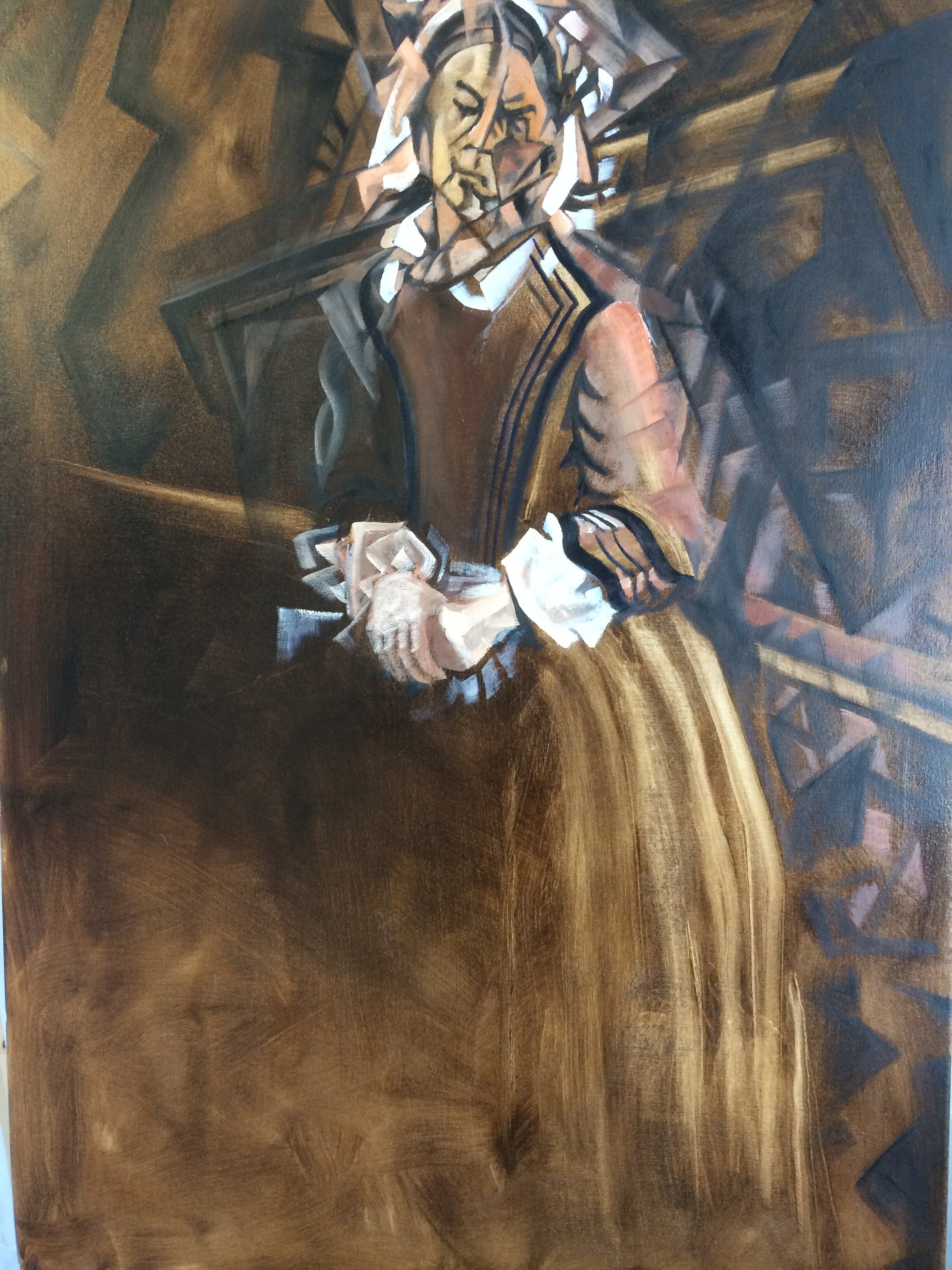

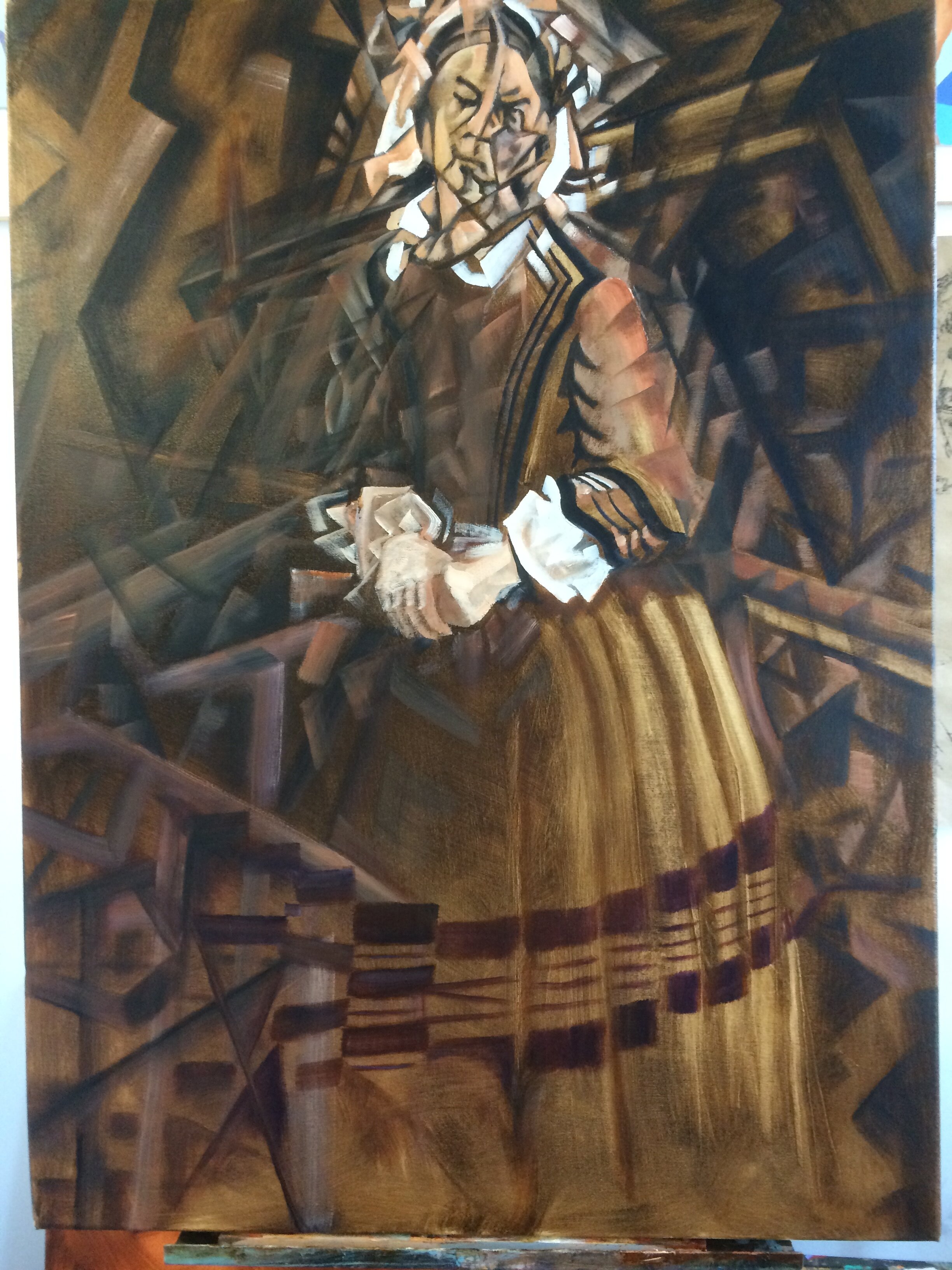

Florence

Nightingale

31.5 x43, oil on canvas, March 2017

Based on Florence Nightingale, Avenging Angel (1998) by Hugh Small,

Florence Nightingale 1820 – 1910 British statistician, social reformer and, and the founder of modern nursing.

She suffered a process of tragic discovery when her own statistical analysis revealed, more than a year after the fact (1856), that thousands of wounded and sick soldiers under her care at the Scutari barracks hospital in Turkey had died from preventable causes. Specifically it showed that due to lack of ventilation and sanitation for the building as a whole, the hospital was a death trap; soldiers closer to the battle front in Crimea and at outlying, more primitive facilities had a much better survival rate. The revelation caused a breakdown, generally agreed upon today as being post-traumatic stress disorder, that sent her temporarily into reclusive solitude. The statistical report she had compiled with Dr. William Farr (a pioneer in epidemiology) was subsequently suppressed by the government. But over the years she repeatedly leaked portions of it to politicians and government ministers to drive forward large-scale public health and hospital sanitary reforms against significant and bitter resistance on the part of the military, medical and political establishment of the time. Her contribution to public health worldwide is immeasurable.

Her book Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not was published in 1859 and has been in continuous print ever since.

Florence Nightingale has been described as having been highly intelligent, deeply religious (she was Anglican but of Unitarian background) and very ambitious. She felt called by God, against her family’s wishes, to become a nurse (in those days not an honorable profession), but this compulsion became tempered by her revelation; “To understand God’s thoughts one must study statistics… the measure of his purpose.”

“My first awareness of Florence Nightingale beyond the “Lady with the lamp” legend was from Lytton Strachey’s portrait of her in his book Eminent Victorians (1918). Although his portrait of her was not altogether flattering, what interested me was her drive and courage in fighting against the fierce resistance to her public health efforts, which Strachey related. Hugh Small’s book made prominent the scientific evidence that supported her vision.

Although she was very much a Victorian (she became a friend of the Queen) her work was thoroughly modern and forward looking. Her colleague in statistical science, William Farr, generated the first actuarial tables in 1864 with the help of a programmable mechanical computer, called the difference engine. This had been developed by the mathematician Charles Babbage in the 1840s. The concept for this machine had been explicated in a set of notes published in 1843. These were written by Ada Byron Lovelace (daughter of the poet) and contained what is considered the first computer program. Florence Nightingale would have been fully aware of these technological advances. Hugh Small has shown that even recently statistical evidence has shown the dramatic rise in life expectancy in England derived from legislation that Nightingale helped to craft.

I have portrayed her in the manner of analytical cubism and Italian futurism, the embrace of modernity and technology in the arts at the culmination of the Victorian era, to reflect her embrace of the most advanced science and technology of her time. In portraying her, I have tried in this way to project the combination of tragic comprehension, compassion, and strength that I have found in her story.”

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910)

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)